Vietnam’s Homegrown RPK, The TUL-1

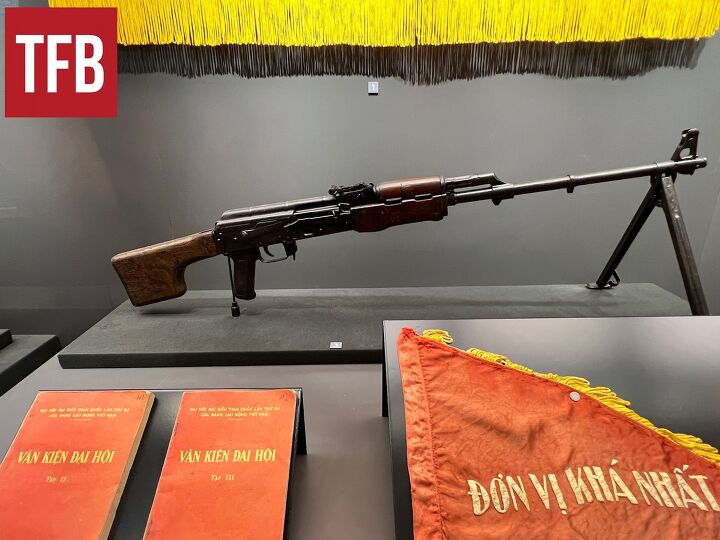

Wandering through the Vietnam Military History Museum in Hanoi, I stumbled upon what looked like an RPK, only to find it was a TUL-1. Vietnam’s own, manufactured RPK. A weapon born out of necessity, ingenuity, and a fair bit of parts-bin creativity.

Born From Self-Reliance

The name TUL-1 comes from Tự Lực, meaning “self-reliance.” And that’s not just a catchy label, it’s the weapon’s entire backstory. In the late 1960s, Vietnam was still deep in the fight against South Vietnam and the United States. Weapons and supplies were coming in from the Soviet Union, China, and other Eastern Bloc allies, but the supply chain was a mess. Even when gear arrived, there was no guarantee that the exact models or numbers needed would appear.

Light machine guns were a prime example. If their other socialist brothers used the RPK, it must be good, right? This was at a time when Vietnam wanted more light machine guns for its infantry doctrine as the war changed from a guerrilla war into a more conventional combined arms war, but RPKs weren’t always available, and Vietnam didn’t yet have the license to build them. So the Ordnance Department and engineers at Z111 Factory (then called Z1 Factory) decided to make their own.

The Gun

The TUL-1 was essentially an RPK clone, but with a twist. Early models used milled Chinese Type 56 receivers before 1974, which gave them a distinct feel compared to the Soviet stamped-receiver RPK. After 1974, production switched to stamped receivers. Early on, there may have been some Chinese assistance in setting up the factory for production prior to the deterioration of relations in 1975. Also, it wouldn’t be a stretch to say there may have been other assistance from other communist bloc nations. Most examples show evidence of being assembled from different salvaged parts.

It wasn’t a direct RPD replacement but filled a gap in the automatic rifle role, giving squads their own automatic rifle when imported RPKs were scarce or non-existent.

Production & Service

The prototype reportedly wrapped up testing in late 1969, and full production began in the early 70s. The stamped TUL-1 production ended sometime in the 70s, but they stayed in service for years, and the stamped version is the rarer of the two. You’d often see them alongside newer RPKs, though the RPD remained the real squad support workhorse.

Even today, a few linger in training and reserve units. Outside Vietnam, stamped-receiver TUL-1s have occasionally popped up in U.S. collections, where they always get a double-take from AK fans. I've personally seen at least two kits that friends were eager to show me.

The TUL-1 is a textbook example of wartime improvisation. It wasn’t just a cheap knock-off but a practical solution built with whatever parts and tooling were available. In that sense, it symbolizes Vietnam’s wartime resourcefulness as those famous Ho Chi Minh sandals were made from recycled tires.

Guns like the TUL-1 also highlight a truth in firearms history: performance isn’t always the deciding factor; logistics, licensing, and politics matter just as much. If you can’t get the weapon you want, you make something that works.

The TUL-1 sits in that sweet spot between rare and functional, especially for those RPK fans. It’s not a one-off prototype; you can find photos of it in the field, but spotting one in person is still a treat. It’s got that “wait, what am I looking at?” factor where your brain sees AK parts but can’t quite place the build. It’ll never have the fame of the AK or RPK, but for those who know the story, it’s worth a nod of respect. Proof that with determination and a bin of mismatched parts, you can keep the bullets flying.

The RPK vs. RPD

The RPK is more of an automatic rifle than a true light machine gun. It just doesn’t bring the same sustained-fire capability as the RPD. U.S. Special Forces in Vietnam seemed to agree; they loved the RPD, often cutting them down for jungle fighting. Many Military Assistance Command, Vietnam – Studies and Observations Group MACV-SOG vets swore by it.

Even today, Vietnamese infantry squads still issue one RPD per nine-man squad. I’d argue they’d be better off with two, one per fire team. When the Soviets ditched the RPD for the RPK, they prioritized parts commonality over capability, leaving their troops without a proper LMG for decades, just like the U.S. did from 1957 to 1984.

In Vietnam, the TUL-1 filled that automatic rifle role for a while; today, the motorized infantry units use RPDs. It’s mostly retired these days, but as a piece of small-arms history, it’s a rare and fascinating relic of late and post-war Vietnam's small arms development.

Lynndon Schooler is an open-source weapons intelligence professional with a background as an infantryman in the US Army. His experience includes working as a gunsmith and production manager in firearm manufacturing, as well as serving as an armorer, consultant, and instructor in nonstandard weapons. His articles have been published in Small Arms Review and the Small Arms Defence Journal. https://www.instagram.com/lynndons

More by Lynndon Schooler

Comments

Join the conversation

Surely someone can make a deal to import some Vietnamese guns.