The Kalashnikovs That Armed Vietnam

The Vietnam War drew in weapons from across the globe, as socialist nations rallied to support their revolutionary ally in the fight for reunification. Among the most significant contributions were the Kalashnikov-based rifles supplied by the Soviet Union and its allies. While traveling across Vietnam, I encountered many of these rifles on display, each representing a unique chapter of the war and international military aid. Here, I'll cover the AKs I could see and give a little overview of the Kalashnikov variants that found their way to the battlefields of Southeast Asia.

The Guns

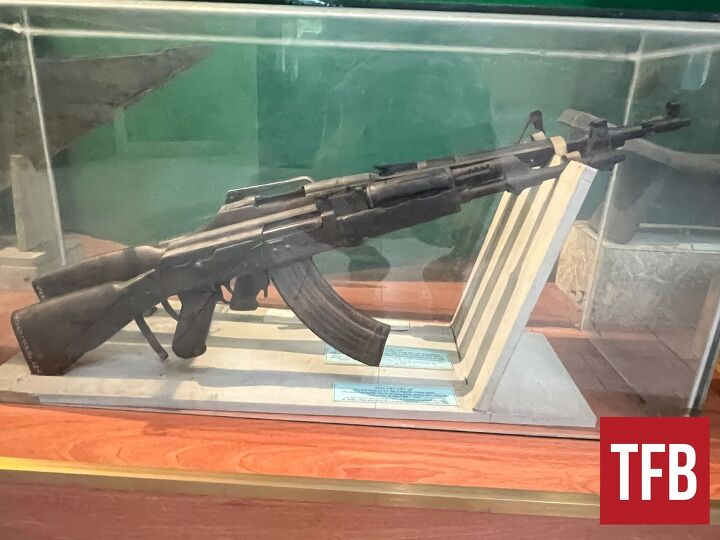

We begin with the Soviet AK Type I, the first generation of the Kalashnikov rifle, a model I saw preserved in Ho Chi Minh City. Produced by Izhmash between 1949 and 1951, the Type I featured a stamped receiver and embodied the rugged simplicity that would become the hallmark of the design. Though initially challenging to produce, it laid the foundation for one of the most iconic firearms in history.

At first, Soviet military aid to North Vietnam was limited, consisting mainly of leftover World War II weaponry. That changed after March 1965, when U.S. Marines landed at Da Nang. Moscow responded by dramatically increasing its support, sending artillery, radar, aircraft, surface-to-air missiles, and, of course, Kalashnikov rifles that would soon become synonymous with communist resistance in Southeast Asia.

The AK Type II appeared in 1951 as the first significant refinement of the design. Manufacturing problems with the Type I’s stamped receiver led Soviet engineers to adopt a heavier but more reliable milled receiver. By 1955, this evolved into the Type III, which shed weight without sacrificing durability. Compact paratrooper versions, like the AKS Type II with its folding stock, were produced in smaller numbers but also made their way to North Vietnam.

Across the Eastern Bloc, allies began producing licensed copies. In Poland, production of the AK Type III began around 1956 at the Fabryka Broni “Łucznik” plant in Radom. Designated the Kbk wz.1960, Poland also fielded a grenade-launching variant, the Kbkg wz.1960. Though Poland had recognized the DRV in 1950, military aid accelerated only after the mid-1960s, when Polish rifles began appearing in Vietnam.

Romania followed in 1963, after securing a license for the AKM. The result was the PM md. 63, built at the Cugir Arms Factory. Romanian arms shipments increased during the late 1960s, and while modest compared to Soviet or Chinese contributions, these rifles still played their part in Hanoi’s arsenal.

Meanwhile, the Soviets introduced the AKM (Avtomat Kalashnikova Modernizirovanniy) in 1959. Lighter, cheaper, and easier to produce, it returned to a stamped receiver, this time perfected. With additions like a slanted muzzle rise compensator and laminated furniture, the AKM became the most widely produced variant.

In East Germany, licensed production began in 1958 with the MPi-K. By the mid-1960s, East German solidarity shipments of weapons, ammunition, and technical equipment reached Hanoi. Many of these rifles remain in Vietnamese museums today, silent witnesses to East German support.

Farther east, North Korea began producing the Type 58, a direct copy of the Soviet Type III, in 1958 at Chongjin. By the mid-1960s, Pyongyang, still hostile to the United States after the Korean War, was sending these rifles to Vietnam in visible solidarity.

Two distinctive variants, the AKM-63 and the AMD-65, came from Hungary. In the late 1950s, Hungary first received a license to manufacture the milled Type III and permission to produce the stamped AKM in 1961. Both were manufactured at the FÉG factory in Budapest. After recognizing the DRV in 1950, Hungary initially offered only political support to it but began sending material aid in the mid-1960s as U.S. involvement escalated.

Bulgaria, too, entered the Kalashnikov brotherhood, receiving a Soviet license in the late 1950s. The AKK, a direct copy of the Type III, was its first standard-issue rifle, followed by stamped AKM variants produced at the Arsenal factory in Kazanlak from the early 1960s. Bulgaria recognized the DRV in 1950 and, by the mid-1960s, was contributing weapons, loans, and supplies alongside its Warsaw Pact allies.

Finally, no discussion of Vietnam War Kalashnikovs is complete without the Chinese Type 56. Licensed in 1955, China began production in 1956, first with milled receivers and later stamped versions. A folding-stock model, the Type 56-1, further expanded the line. The export version of the Type 56, the M22, was also used during the war. Chinese support to Vietnam began during the First Indochina War. It expanded massively after 1965, making the Type 56 one of the most recognizable weapons of the conflict, carried by both the People’s Army of Vietnam and the Viet Cong.

Final Thoughts

From Soviet first generation to Chinese mass production, the Kalashnikov family of rifles became a defining feature of the Vietnam War. Each national variant tells part of the story of how Cold War alliances shaped one of the 20th century’s most intense conflicts.

The Vietnam War was the proving ground where the Kalashnikov established its global reputation. From Soviet AKs to Eastern European licensed models and Chinese mass production, these rifles reflected not only Soviet engineering but also the solidarity of the socialist bloc. Flowing into Vietnam through intricate supply networks, they armed both the People’s Army and the Viet Cong with reliable, battlefield-proven weapons.

Though they differed in details, milled or stamped receivers, national markings, or unique adaptations like Hungary’s AMD-65, all Kalashnikovs shared a common lineage that made them a formidable asset on the battlefield. Their widespread presence in Vietnam reveals the globalization of the AK, transforming it from a Soviet service rifle into a worldwide symbol of revolution and resistance.

By the war's end, the Kalashnikov was more than a weapon; it was an instrument of ideology, a bond of solidarity, and an enduring icon of one of the Cold War’s defining struggles.

Lynndon Schooler is an open-source weapons intelligence professional with a background as an infantryman in the US Army. His experience includes working as a gunsmith and production manager in firearm manufacturing, as well as serving as an armorer, consultant, and instructor in nonstandard weapons. His articles have been published in Small Arms Review and the Small Arms Defence Journal. https://www.instagram.com/lynndons

More by Lynndon Schooler

![[IDEF 2025] PZD MK1 - Combat-Proven Machineguns From Czechia](https://cdn-fastly.thefirearmblog.com/media/2025/07/24/00501/idef-2025-pzd-mk1-combat-proven-machineguns-from-czechia.jpg?size=350x220)

Comments

Join the conversation

The Soviets never gave their TDP for the AKM to the Chinese. Mao Zedong was not happy with the anti Stalinist reforms in the Soviet Union and friction between the two nations increased. The Chinese tried to reverse engineered The AKM, but used a thicker sheet metal for the receiver. This resulted in a sturdier lower that they deemed wouldn't need the (so called) 5 piece rate reducer that was in reality an anti bounce device.