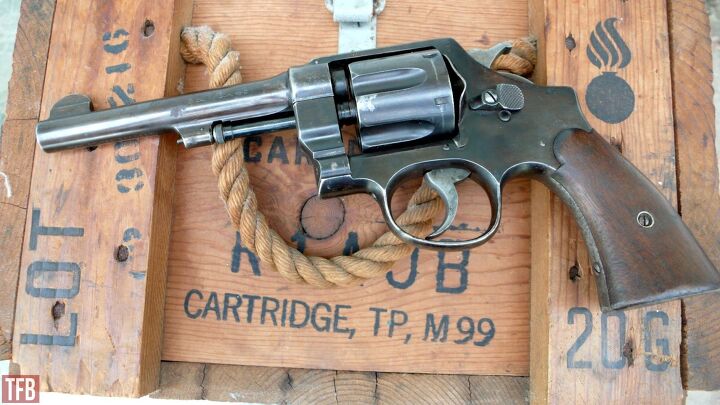

Wheelgun Wednesday: S&W Model 1917 - The GOAT Military Revolver

You could argue what classic military semi-auto pistol was the best. The Browning Hi-Power has a lot going for it. So does the Colt Model 1911. The Luger P08 scores a lot of style points; the Walther P38 wins on features. But if you’re talking about military revolvers, there’s only one that combines effectiveness with a long lifespan in military arsenals of a wide variety of users. Based on that criteria, the Smith & Wesson Model 1917 is the greatest military revolver of all time, and it’s not even close.

Mil-Surp Six-Shooters @ TFB:

A Stop-Gap Measure

Smith & Wesson never set out to build the Model 1917 of their own volition, not exactly. As the name implies, the Model 1917 came into being in the middle of the 1914-1918 stretch of World War 1. In 1917, the U.S. entered the war as a wild card to help the Entente blow the Western Front wide open (or at least, that’s what was hoped). The States had recently adopted the Colt Model 1911 as its standard sidearm, but they needed to arm a lot of new soldiers very quickly, and the logistics wonks didn’t think they could get enough of the new semi-autos to their doughboys in France quickly enough. Why not order a bunch of revolvers, too? After all, a six-shooter was better than having nothing in hand but an entrenchment tool and a harsh word in a midnight trench raid.

So, the U.S. military went to both Colt and Smith & Wesson, ordering new revolvers from each, and giving them both the same name, although they were completely different. Colt’s Model 1917 appeared here in a previous Wheelgun Wednesday write-up. I don’t have much to say about it other than most people seem to think they’d rather have the Smith & Wesson revolver. The Colt seems to be regarded as less robust.

For both companies, the government orders were relatively easy to kick into production, because both companies just recycled previous revolver designs. In Smith & Wesson’s case, they had just sold thousands of Hand Ejector revolvers chambered in .455 Webley to the Canadian and British armies, who were proving their capability in the trenches already. All Smith & Wesson had to do was chamber the cylinders in .45 ACP, and they had a revolver they knew would work well. The Allied Powers were already proving it.

Although it was based on the Hand Ejector design, the Model 1917 was not a Triple Lock design. After feedback from the Brits and the Canadians, Smith & Wesson’s military revolvers had no cylinder crane lock or barrel lug; this supposedly removed one of the potential failure points on the action and also made the revolver cheaper to sell. Cheaper weapons are always welcomed by governments in wartime, or at least they were welcomed before the military-industrial complex began running the show in the West after World War II.

There was another, even larger design change than the removal of the lock. The Brits and Canadians ordered revolvers in .455 Webley, a rimmed cartridge, that the star ejector could easily clear from the cylinder. The U.S. government wanted their revolvers chambered in the rimless .45 ACP. Smith & Wesson bored the cylinders to allow the cartridge to headspace on the case mouth. To facilitate ejection, they invented the half-moon clip. These stamped-out pieces of sheet metal, shaped like a half-moon, held three cartridges in a semicircle. They made it quicker to load the revolver, and when it was time to unload, the ejector could push out the half-moon clip and the casings attached to it.

See the half-moon clips shown in the YouTube clip below, on a Colt Model 1917. Although it was a different revolver entirely, the Colt faced the same problem with rimless cartridges and had the same solution (borrowed from Smith & Wesson, who let them use the design free of charge):

Although the Smith & Wesson and Colt were both intended only to augment the 1911 in World War I, and bring arsenal numbers up as a stopgap measure, the U.S. ordered a whopping 300,000 of these revolvers in total, roughly 150,000 from each manufacturer. Many of these handguns never made it to the front, as the Central Powers collapsed earlier than expected, but they had a lot of service life left at this point.

The Inter-War Order

As war drums beat around the globe through the 1930s, militaries started stockpiling weapons and looking to improve their arsenals. In 1937, despite the global move to semi-auto pistols, the Brazilian military decided to order 25,000 Model 1917 revolvers in .45 ACP. Although this is only a small fraction of the number of Model 1917 revolvers sold, many of these came back to North America as surplus, and they were often available for less money than their General Issue counterparts. But it’s worth noting that although South America is not generally considered to have much to do with World War II, these revolvers would indeed have their own chance at a shooting war when the Brazilian Expeditionary Force participated in the Italian Campaign.

World War II Remobilization

Most of the Model 1917 revolvers were supposedly issued to rear echelon troops in World War II—home guard roles, or military policemen. However, plenty did see action in the European and Pacific theatres. They popped up in war movies sometimes, too—most famously in the 2014 tanker combat flick Fury, where Don "Wardaddy" Collier wields one with see-through sweetheart grips. In the real world, perhaps the most famous user in World War II was General Mark Clark—his old service revolver was sold by Morphy’s back in 2018.

After The Big One

With two world wars under its belt, surely it was time to retire the old warhorse, right? Not so. The Model 1917 stayed in use through the Korean War and even Vietnam; the revolver was reportedly issued right up until the late 1970s, when it was retired. It would be completely unsurprising to find a few still kicking around a forgotten government stockpile somewhere, as they found use outside military duty as well, including work in the U.S. Postal Service, arming guards. Police departments bought them, too, and civilians.

With military usage across multiple theaters of war, by countries in Europe, South America and North America, and service over 60 years that started with cavalry charges and ended with helicopters, it is hard to argue that any other revolver has the same job record as the Model 1917 S&W—and by that standard, it is the greatest military revolver of all time.

Buying a Model 1917 today

There are many of these revolvers available on the used market. Keeping in mind that there is lots of money to be made counterfeiting USGI markings and pretending some revolver was used to shoot a hundred and fifty enemies in a last-ditch fight in the Battle of the Bulge or whatever, you definitely want to know your stuff before bidding or buying one. Prices seem to range all over, from under $500 to more than $2,500.

See here for an example at Guns International—again, do your homework before you buy anything like this. But if you find one you like, one last thing: If you buy one of these older revolvers, you don’t have to mess around with the half-moon clips if you don’t want to. The .45 Auto Rim cartridge, developed after World War I by the Peters Cartridge Company, is the same as .45 ACP, but with a rimmed casing that the S&W’s extractor can manipulate, without needing to use the clips. You can still buy .45 Auto Rim brand-new; it’s not cheap, but it might be preferable for some users.

Comments

Join the conversation

I carried a Mod. 10, at my PD, until the mid 2000’s.

I have one of the 1937 Brazilians. I shoot it frequently & enjoy it although the rifling is shallow & not the best for cast lead bullets. Enjoyed the article but, please, please use correct terminology since we are gun folks --- It's "case" not casing when referring to cartridges. Casing is sausage covering or pipe used in oil wells! This is a pet peeve amongst professional firearms examiners!