Captured U.S. Weapons In Vietnam And How They Nudged Soviet Design

The Vietnam War was fought not only with bullets and bombs but also with information. One of the lesser-told stories of that conflict is how battlefield captures, salvage, and plain curiosity about enemy hardware gave the Soviets, via North Vietnamese channels, a valuable window into American small arms, explosives, and other systems, in theory closing a technological capability gap. Physical specimens spoke plainly where political and human intelligence met limits: engineers could disassemble, measure, test, and imagine what a given system might mean for their own forces. The result was rarely wholesale copying; it was selective borrowing, finding what worked, adapting it to Soviet doctrine, and folding useful ideas into existing design philosophies.

Captured U.S. weapons reached Soviet evaluators by several surprisingly direct routes. Some were handed over to visiting Soviet military delegations by Hanoi; others were examined on-site by allied engineers. Photographs, component parts, and technical descriptions were routed through diplomatic channels or moved directly via intelligence operations to collect anything of value from U.S. military assets. This effort appears to have involved elements of the Soviet Military Advisory Corps in Vietnam and a dedicated military-scientific team, informally known as the “trophy men.” Sent to Vietnam by the GRU of the USSR General Staff, the five-person team consisted of civilian defense-industry specialists led by the Main Intelligence Directorate and also by the 10th Main Directorate of the General Staff. Their work included preliminary study of captured equipment and ammunition, disposal of unexploded ordnance, selection and procurement of representative samples, and shipment of those specimens back to the Soviet Union. Once in hand, Soviet designers could perform metallurgical analyses, conduct ballistics and range trials, and translate empirical findings into concrete design changes.

M72 LAW

Several high-profile examples illustrate this dynamic. The U.S. M72 LAW (Light Anti-tank Weapon), a single-shot disposable rocket launcher used in Vietnam, stands out as an influence on later Soviet light anti-tank rocket designs such as the RPG-18, which entered service in 1972. The LAW’s compact, throwaway nature and tactical role, close support, one-man portability, and rapid employment, matched an operational need Soviet planners were increasingly conscious of. That convergence of requirement and captured evidence helped spur the development of compact, shoulder-fired rockets in the same conceptual space.

M18 Claymore

Directional anti-personnel mines provide another clear line of inspiration. The U.S. M18 Claymore, with its frontal blast pattern and emphasis on standoff placement, reshaped thinking on area denial and ambush tactics. Soviet engineers and planners took notice: directional fragmentation and controlling lethal arcs proved tactically valuable for defense and ambushes. The MON-series of Soviet directional mines echoes that logic in purpose, if not in exact form. The MON-50’s presence in Soviet arsenals by the mid-1960s suggests that examples, captured from U.S. advisors, indeed, were captured before official full-scale U.S. combat deployment.

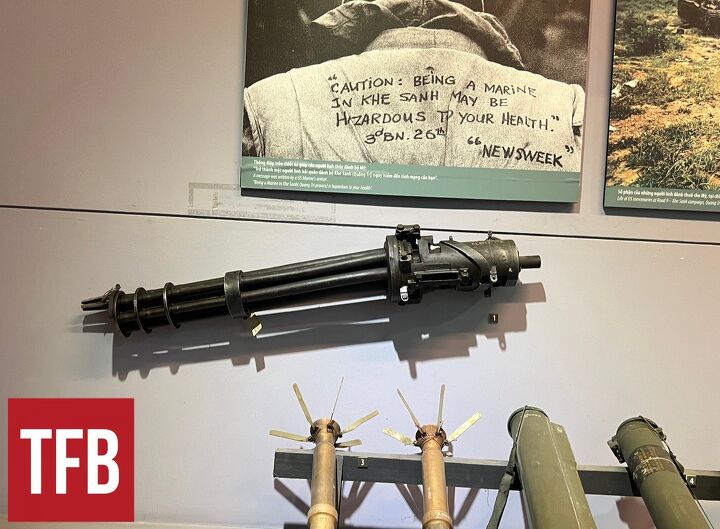

GAU-2

Rotary multi-barrel weapons likewise drew close scrutiny. The U.S. GAU-2 family, better known in service as the M134 Minigun, demonstrated the tactical advantages of extremely high rates of fire for helicopters and gunships. Soviet designers pursued a similar high volume of fire solutions for aircraft and rotary platforms. This cross-pollination is less an accusation of copying than evidence of parallel problem-solving once the advantages became evident: captured examples and combat reports contributed to developing and adopting systems such as the GShG-762, which Soviet sources fielded around 1970.

M60 Flash Hider

Not every captured system produced a one-for-one Soviet counterpart, but even those that didn’t could leave a technical mark. Soviet experts assessed the U.S. M60 general-purpose machine gun. At the same time, the M60’s overall architecture did not displace Soviet machine-gun doctrine; components like the M60 flash hiders were studied and adapted for the PKM machine gun in development to meet Soviet requirements, as covered in my previous article. Photographs and recovered specimens from early in the conflict show captured M60s as early as 1962; the PKM, adopted in 1969 and notable for its long M60-like flash hider, reflects how individual features can travel independently of whole-system adoption.

5.56x45mmm Cartridge

A strategically significant influence was the U.S. adoption of the smaller-caliber, high-velocity .223 Remington (5.56x45mm) cartridge. Soviet observation of U.S. trends in the early 1960s, amplified by captured ammunition and weapons, helped convince Soviet planners that a lighter, high-velocity intermediate or micro caliber could improve controllability, reduce soldier loadout weight, and improve hit probability. That perception was one factor among several that eventually led to the development and fielding of the 5.45x39mm cartridge adopted in 1974 and its associated small-arms families in later decades. The process was evolutionary rather than a copy-and-paste: battlefield exposure turned theoretical debate into demonstrable, measurable effects.

XM191/XM202

The transfer of technology extended into more exotic categories as well. Experimental U.S. concepts, rocket-launched incendiary designs, and advanced shoulder-fired munitions were particularly interesting. With steady flows of technology and intelligence during the conflict, it is plausible that systems such as the XM191/XM202 sparked interest in developing counterparts. By 1975, Soviet work on compact, thermobaric shoulder systems, exemplified in adoption like the MO-25 Lynx, reflected an enduring fascination with man-portable thermobaric and thermobaric-like rocket launchers.

Even where a working U.S. prototype did not reach Soviet laboratories, fragments, technical descriptions, or photographs could seed new lines of research. Where direct evidence exists, a pattern emerges: Soviet designers repeatedly sought comparable capabilities within their industrial base and doctrine constraints. The emergence of Soviet compact rocket launchers and thermobaric-like shoulder systems is consistent with a measured response to observed U.S. experimentation and battlefield employment. The U.S. experiments with belt-fed grenade launchers may have encouraged the Soviets to push forward with the AGS-17. However, the idea was originally Soviet, the Taubina AG-2 grenade launcher; seeing U.S. interest likely gave it extra impetus.

It is important to be precise about causation: not every Soviet weapon that resembled a U.S. system sprang from captured materiel. The Cold War arms race was a dialogue of parallel needs and parallel solutions. But captured U.S. hardware created moments of clarity. When engineers could hold, turn, and fire a counterpart’s device, abstract ideas became concrete, and that tactile intelligence shortened development timelines and sharpened priorities.

Conclusion

By the end of the conflict and in its immediate aftermath, the lessons of Vietnam had penetrated Soviet military thought. Whether through imitation, selective adoption, or simply by refining what modern infantry and aviation systems needed to do, captured U.S. hardware nudged Soviet designs in measurable ways. The story is a reminder that technological influence in war is rarely unidirectional; it is a continuous, iterative conversation in which battlefield experience and physical specimens play an outsized role.

Lynndon Schooler is an open-source weapons intelligence professional with a background as an infantryman in the US Army. His experience includes working as a gunsmith and production manager in firearm manufacturing, as well as serving as an armorer, consultant, and instructor in nonstandard weapons. His articles have been published in Small Arms Review and the Small Arms Defence Journal. https://www.instagram.com/lynndons

More by Lynndon Schooler

![[IDEF 2025] PZD MK1 - Combat-Proven Machineguns From Czechia](https://cdn-fastly.thefirearmblog.com/media/2025/07/24/00501/idef-2025-pzd-mk1-combat-proven-machineguns-from-czechia.jpg?size=350x220)

Comments

Join the conversation

Telegram: @plugg_drop, How i buy Marijuana in Dubai, read full story .

I was seat in MAYBACK with 3 naked girls , one of them told me that to just wait lil we will be at the store house .They located under the building the place is very silent, they delivery Wild Plant in Muscat 24/7 Give them your delivery adress . The payment process in Dubai is fastly. In Oman , they use Cryptocurenccies like USDT , TRONX, Ethereum, … you can also use your Visa Card for buy Exotics in Salalah. Don’t worry about buy Xanax in Qurayyat Inbox @plugg_drop with telegram app.

the rpg 2 and 7's were better then our Law.

We got so many duds delivered to our armored cav unit that we would take them out and blow them all up. that was in 1968.